Mandiant APT1 Report Has Critical Analytic Flaws

From: Digital Dao

by Jeffrey Carr

Mandiant’s APT1 report is the latest infosec company document to accuse the Chinese government of running cyber espionage operations. In fact, according to Mandiant, if a company experiences an APT attack, then it is a victim of the Chinese government because in Mandiant-speak, APT equals China.

“We tend to perceive what we expect to perceive”

– Richard J. Heuer, “The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis

The fact that Mandiant refuses to acknowledge that other nation states engage in cyber espionage when the facts show otherwise demonstrates what Heuer calls an “expectation bias”, but it’s much worse than that.

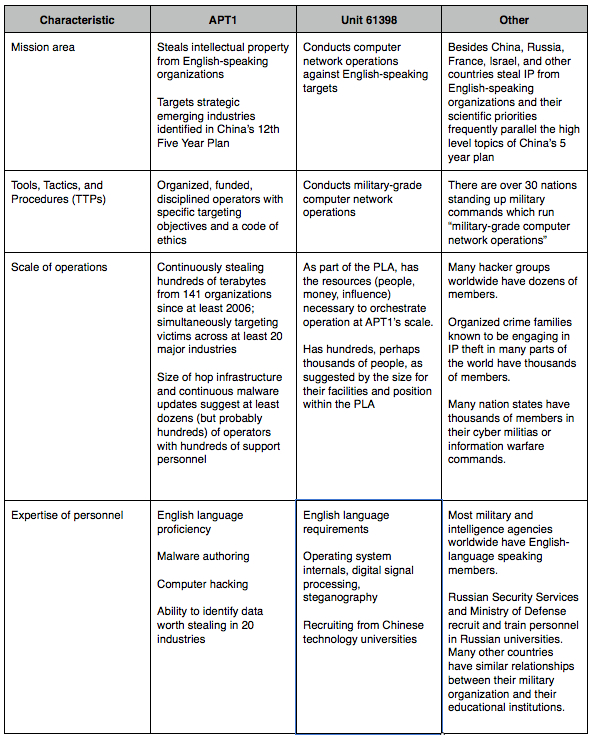

Mandiant’s alleged proof is summarized in Table 12 (pp. 59-60): “Matching characteristics between APT1 and Unit 61398”. Mandiant’s entire premise that APT1 is PLA Unit 61398 rests on the connections made in that table and that no other conclusion is possible:

“Combining our direct observations with carefully researched and correlated findings; we believe the facts dictate only two possibilities: Either a secret, resourced organization full of mainland Chinese speakers with direct access to Shanghai-based telecommunications infrastructure is engaged in a multi-year, enterprise scale computer espionage campaign right outside of Unit 61398’s gates, performing tasks similar to Unit 61398’s known mission or APT1 is Unit 61398.” (APT1, p. 60)

If this report were written by a professional intelligence analyst at CIA, it would most likely undergo a vetting process known as ACH (Analysis of Competing Hypotheses):

“Analysis of competing hypotheses, sometimes abbreviated ACH, is a tool to aid judgment on important issues requiring careful weighing of alternative explanations or conclusions. It helps an analyst overcome, or at least minimize, some of the cognitive limitations that make prescient intelligence analysis so difficult to achieve.”

In other words, ACH forces the intelligence analyst to look for all alternative hypotheses and assess them one at a time to see which best fits the data collected. This is rarely if ever done by information security companies, and it’s the single biggest objection that I have when it comes to individuals making claims of attribution to nation states. Heuer’s iconic “Psychology of Intelligence Analysis” explains why ACH is so important:

“The way most analysts go about their business is to pick out what they suspect intuitively is the most likely answer, then look at the available information from the point of view of whether or not it supports this answer. If the evidence seems to support the favorite hypothesis, analysts pat themselves on the back (“See, I knew it all along!”) and look no further. If it does not, they either reject the evidence as misleading or develop another hypothesis and go through the same procedure again. Decision analysts call this a satisficing strategy. (See Chapter 4, Strategies for Analytical Judgment.) Satisficing means picking the first solution that seems satisfactory, rather than going through all the possibilities to identify the very best solution. There may be several seemingly satisfactory solutions, but there is only one best solution.”

“Chapter 4 discussed the weaknesses in this approach. The principal concern is that if analysts focus mainly on trying to confirm one hypothesis they think is probably true, they can easily be led astray by the fact that there is so much evidence to support their point of view. They fail to recognize that most of this evidence is also consistent with other explanations or conclusions, and that these other alternatives have not been refuted.”

If Mandiant or another organization were to use ACH on this evidence, here’s how Heuer recommends it be done. It’s an 8-step process:

1. Identify the possible hypotheses to be considered. Use a group of analysts with different perspectives to brainstorm the possibilities. 2. Make a list of significant evidence and arguments for and against each hypothesis. 3. Prepare a matrix with hypotheses across the top and evidence down the side. Analyze the “diagnosticity” of the evidence and arguments–that is, identify which items are most helpful in judging the relative likelihood of the hypotheses. 4. Refine the matrix. Reconsider the hypotheses and delete evidence and arguments that have no diagnostic value. 5. Draw tentative conclusions about the relative likelihood of each hypothesis. Proceed by trying to disprove the hypotheses rather than prove them. 6. Analyze how sensitive your conclusion is to a few critical items of evidence. Consider the consequences for your analysis if that evidence were wrong, misleading, or subject to a different interpretation. 7. Report conclusions. Discuss the relative likelihood of all the hypotheses, not just the most likely one. 8. Identify milestones for future observation that may indicate events are taking a different course than expected.

I don’t have the time to run Mandiant’s evidence through an ACH process but I’d like to propose that a volunteer group of intelligence students at Mercyhurst Institute of Intelligence Studies do that very thing. My friend Professor Kris Wheaton who teaches there and writes the outstanding Sources and Methods blog is an expert in this area and I’m hopeful that he’ll pick up the challenge.

In the meantime, the following table has four columns. The first three are from Mandiant’s table 12. The “Other” column contains a partial group of alternatives that I’ve provided for each of Mandiant’s “characteristics”. These alternatives need to be analyzed and ruled out using a rigorous analytic process like ACH before Mandiant or anyone else can claim that APT1 is a part of China’s Peoples Liberation Army.

In summary, my problem with this report is not that I don’t believe that China engages in massive amounts of cyber espionage. I know that they do – especially when an executive that we worked with traveled to Beijing to meet with government officials with a clean laptop and came back with one that had been breached while he was asleep in his hotel room.

My problem is that Mandiant refuses to consider what everyone that I know in the Intelligence Community acknowledges – that there are multiple states engaging in this activity; not just China. And that if you’re going to make a claim for attribution, then you must be both fair and thorough in your analysis and, through the application of a scientific method like ACH, rule out competing hypotheses and then use estimative language in your finding. Mandiant simply did not succeed in proving that Unit 61398 is their designated APT1 aka Comment Crew.

| Print article |