From: Mercatus Center/George Mason University

Hester Peirce, Robert Greene

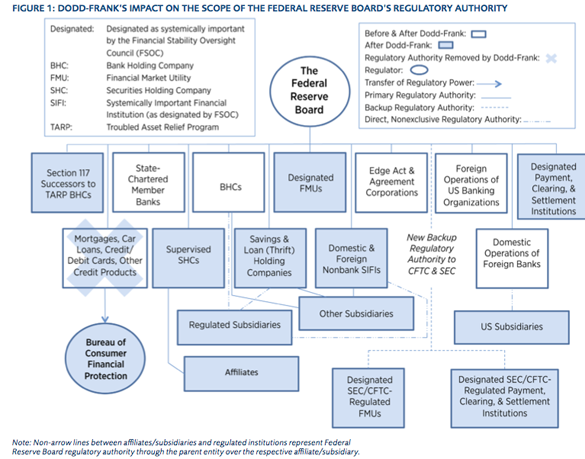

The Federal Reserve’s performance as a regulator in the years leading up to the 2007–08 crisis earned it widespread criticism. In the wake of the crisis, its fate as a regulator was uncertain as Congress considered regulatory reforms. Some reform proposals would have substantially diminished the Federal Reserve’s regulatory role, but the financial reform ultimately signed into law in July 2010—Dodd- Frank—instead increased the Federal Reserve’s regulatory power.

While the Federal Reserve, the nation’s century- old central bank, is primarily known for its monetary policy responsibilities, it also exercises substantial regulatory powers. The Federal Reserve System consists of the seven-member Board of Governors (Board), supported by a staff of 2,400, and twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, with their own boards of directors and a combined staff of more than 15,500.[1] The governors are presidentially nominated and Senate-confirmed and fill staggered fourteen-year terms. Few appointees serve a full term. From among the governors, the president nominates and the Senate confirms a chairman and two vice-chairmen to serve four-year terms. Dodd- Frank added the second vice-chairman position to oversee the Board’s supervision and regulation functions. The Federal Open Market Committee, which comprises the Board and certain Federal Reserve Bank presidents, makes monetary policy decisions.

As will be discussed below, the Board supervises and regulates an increasing number of companies. In its regulatory capacity, the Board writes prudential rules, imposes reporting and record-keeping obligations, approves or disapproves activities, conducts examinations, and brings enforcement actions. The Board delegates some of these responsibilities—particularly examinations—to the regional Reserve Banks.

BANKS

The Board supervises and regulates state-chartered commercial banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System. Dodd-Frank did not alter the Board’s authority over these banks, of which there were 828 at the end of 2011.[2] Nationally chartered banks continue to be primarily regulated by a separate agency, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is the principal federal regulator for state banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System.

BANK HOLDING COMPANIES

The Federal Reserve Board supervises and regulates all US bank holding companies, including financial holding companies. There were 5,341 bank holding companies—companies that own or control one or more banks—at the end of 2011.[3] Dodd-Frank enhanced the Board’s authority over bank holding companies.

1. Dodd-Frank requires the Board to subject bank holding companies with more than $50 billion in assets to “more stringent” prudential standards than apply to other bank holding companies.[4] These standards must include risk-based capital requirements, leverage limits, liquidity requirements, risk-management requirements, resolution plan and credit exposure report requirements, and limits on credit exposure to other companies. The Board also may impose contingent capital requirements, enhanced public disclosures, short- term debt limits, and other prudential standards.

2. Dodd-Frank expands the Board’s authority over the whole holding company structure, including subsidiaries—even subsidiaries that have another regulator. Dodd-Frank broadened the Board’s ability to write rules for, impose reporting obligations on, examine the activities and financial health of, and bring enforcement actions against subsidiaries, including entities regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and state-regulated entities.[5] The Board must attempt to avoid duplicating the primary regulator’s work.[6] Dodd-Frank requires the Board to examine activities of unregulated subsidiaries.[7] Dodd-Frank’s requirement that holding companies serve as a source of strength for their depository subsidiaries gives the Board additional regulatory power over bank holding companies.[8]

SAVINGS AND LOAN HOLDING COMPANIES

Dodd-Frank eliminated the Office of Thrift Supervision and split its regulatory authority among the Board, the OCC, and the FDIC. Regulatory authority over savings and loan (thrift) holding companies and their non-depository subsidiaries went to the Board.[9] The Board’s regulatory approach to savings and loan holding companies is patterned on its supervision of bank holding companies, and savings and loan holding companies must serve as a source of strength for their thrift subsidiaries. As of mid-2011, there were 427 savings and loan holding companies.[10]

SECURITIES HOLDING COMPANIES

Prior to Dodd-Frank, an investment bank holding company that owned or controlled a broker or dealer and was not affiliated with a bank could apply to the SEC for comprehensive consolidated supervision in order to satisfy foreign regulatory requirements. Dodd-Frank gives the Board consolidated supervision authority for securities holding companies—companies that own or control one or more SEC-registered brokers or dealers.[11] A securities holding company regulated by the Board will “be supervised and regulated as if it were a bank holding company.”[12] To date, there are no securities holding companies supervised by the Board.

DESIGNATED NONBANK FINANCIAL COMPANIES

Dodd-Frank gives the Board regulatory authority over nonbank financial companies designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). The FSOC is authorized to designate domestic and foreign companies “predominantly engaged in financial activities” such as insurance and investment activities that “could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States.”[13] Dodd-Frank directs the Board to determine by rule what it means to be predominantly engaged in financial activities.[14] Although no entity has yet been designated, several are under consideration.

Designated nonbank financial companies will be subject to heightened prudential regulatory standards, which are likely to be similar to those applicable to large bank holding companies.[15] Dodd-Frank gives the Board authority to regulate the financial activities of nondepository subsidiaries of designated nonbank financial companies.[16]

TARP-RECIPIENT BANK HOLDING COMPANIES

Dodd-Frank included a provision to ensure that the Board retains regulatory authority over bank holding companies with more than $50 billion in assets as of January 1, 2010, that participated in the Capital Purchase Program under the Troubled Asset Relief Program.[17] Even if they cease to be bank holding companies, Dodd-Frank directs the Board to treat them like designated nonbank financial companies. To date, there are no companies in this category.

DESIGNATED FINANCIAL MARKET UTILITIES AND ACTIVITIES

Dodd-Frank also empowers the FSOC to designate “financial market utilities” and payment, clearing, and settlement activities that it “determines are, or are likely to become, systemically important.”[18] Designated financial market utilities and financial institutions engaging in designated activities are subject to enhanced regulation by the Board. With respect to financial market utilities or financial institutions regulated by the SEC or the CFTC, the Board plays a backup regulatory, examination, and enforcement role.[19] The FSOC has designated eight systemically important financial market utilities. The Board serves as primary regulator for CLS Bank International—which operates a cash settlement system for foreign exchange transactions—and The Clearing House Payments Company—which operates the Clearing House Interbank Payments System, known as CHIPS. The FSOC has not designated any payment, clearing, or settlement activities.

INTERNATIONAL BANKING ACTIVITIES

Dodd-Frank did not alter the Board’s supervisory authority over Edge Act and agreement corporations, which are chartered by the Board and states respectively to engage in international banking transactions. As of the end of 2011, there were 48 Edge Act/agreement corporations.[20 ]Dodd-Frank also did not affect the Board’s oversight of domestic banks’ foreign operations.

US OPERATIONS OF FOREIGN BANKS

Prior to Dodd-Frank, the Board had authority over the US operations of foreign banking organizations—of which there were more than 200 as of September 30, 2012.[21] Dodd-Frank enhanced the Board’s authority to impose prudential regulations on large foreign banking organizations.[22] A recent Board proposal includes heightened prudential standards for large foreign banking organizations and a requirement that certain foreign banking organizations establish separately capitalized intermediate holding companies, which would contain all US subsidiaries.[23]

FINANCIAL STABILITY

Dodd-Frank expanded the Board’s discretionary authority with a nebulous mandate to consider risk to the financial system in different contexts, such as merger and acquisition approvals and divestitures.[24]

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Prior to Dodd-Frank, the Board was the regulator primarily charged with promulgating consumer financial protection regulations, but it shared examination and enforcement responsibilities. Dodd-Frank transferred most of the Board’s consumer financial protection responsibilities to the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection.[25] The Bureau, although technically housed within and funded by the Federal Reserve System, is independent from the Board.[26] Consumer regulation is, therefore, one area in which the Board lost regulatory authority under Dodd-Frank.

CONCLUSION

Dodd-Frank did not—as some policy analysts pro- posed or expected—decrease the Federal Reserve Board’s regulatory powers. To the contrary, it gave the Board heightened regulatory authority over certain entities it previously oversaw, and new regulatory authority over entities it did not previously regulate. The Board has demonstrated an intent to exercise this authority aggressively and an interest in gaining new authority. The magnitude of the Board’s new powers is indicated by the fact that it has employed 964 employees on Dodd-Frank implementation, which exceeds the staff commitment made by any other regulator.[27] Legislators and other policymakers should continue to evaluate whether the increasingly Federal Reserve-centric allocation of regulatory power and the Board’s broad rulemaking discretion is the optimal regulatory structure for the diverse financial services sector.